Knowledge and Beliefs about Cervical Cancer Screening among Insured Women Living in the US-Mexico Border City of El Paso

Ruth Forde*

Department of Family and Community Medicine, TTUHSC El Paso, El Paso, Texas

*Corresponding author: Ruth Forde, Department of Family and Community Medicine, TTUHSC El Paso, El Paso, Texas, E-mail: ruthforde77@gmail.com

Received date: March 1, 2022, Manuscript No. IPJPM-22-12679; Editor Assigned date: March 3, 2022, PreQC No. IPJPM-22-12679(PQ); Reviewed date: March 17, 2022, QC No. IPJPM-22-12679; Revised date: March 23, 2022, Manuscript No. IPJPM-22-12679(R); Published date: March 30, 2022, DOI: 10.36648/2572-5483.7.5.126

Citation: Forde R (2022) Knowledge and Beliefs about Cervical Cancer Screening among Insured Women Living in the US-Mexico Border City of El Paso. J Prev Med Vol.7 No.5:126

Abstract

Background: In August of 2018 USPSTF published its final recommendation on cervical screening for average risk women. The recommendations were: no screening for women less than 21, cervical cytology (pap smear) alone every 3 years for women 21-29, and for women 30-65 cervical cytology (pap smear) alone every 3 years or hrHPV testing alone every 5 years or Co-testing (hrHPV+cervical cytology) every 5 years. These recommendations were the product of a manner to balance the benefit (disease detection) and potential harms (unnecessary treatment in women with false positive results).

Purpose: This study investigated if women who are insured and living in the US-Mexico border city of El Paso undergo more frequent pap smear screening than the recommended guidelines. It also assessed women’s understanding about cervical screening and the format in which they would most prefer to receive educational material about cervical cancer screening

Methods: 80 female participants at an outpatient primary care clinic in El Paso, age 21-65, who came in for routine care and gave consent to complete an office-based survey on understanding cervical cancer screening. The survey assessed how often the participants obtained a pap smear, their reason for getting it done that often. It also assessed their understanding of HPV and the role it plays in cervical cancer screening.

Results: Out of the 80 female participants (age 21-65), 94% had a pap smear in their lifetime and 6% never had a pap smear; 48% of those who had a pap smear reported getting yearly paps regardless of age (ranging from age 22-65) and 20% reported every 2 years, bringing the percentage of women who undergo cervical cancer screening every 1 to 2 years to 68%. 25% reported screening every 3 years and only 3% stated screening every 5 years. Responses for why patient screened more frequently were “my doctor tells me to,” “peace of mind,” “force of habit,” “history of abnormal paps,” and “no such thing as too often.” Most of the participants (63%) preferred to receive information about cervical cancer screening by having dedicated time for discussions with the provider the day of the Pap smear, 38% wanted printed materials or brochure and 18% wanted a short video the day of the Pap smear.

Conclusion: Findings revealed that women continue to undergo more frequent cervical cancer screenings than the recommended guidelines with main reason cited as “my doctor tells me to,” at 43% suggesting a barrier to less frequent screening not only on the patient’s side but on the provider’s side as well. The participants also desired more education about pap smear/cervical cancer screening, of which the most desired educational format is dedicated time for discussions with the provider on the day of the pap smear.

Introduction

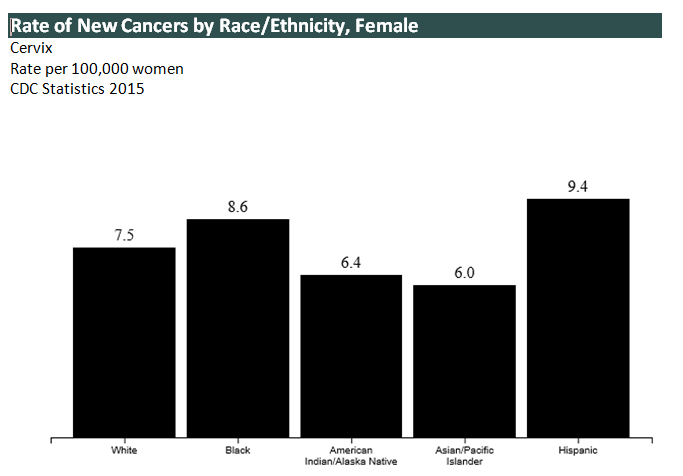

In 1941 the Papanicolaou (pap smears) test, screening for cervical cancer was introduced in the United States. The goal of cervical cancer screening is to detect precancerous lesions found by pap smears before it becomes advanced. These abnormal cells can be treated and cured before they develop into cancer. Cervical cancer used to be the leading cause of cancer death for women in the United States. However, in the past 40 years, the number of cases of cervical cancer and the number of deaths from cervical cancer have decreased significantly due to cervical cancer screening. The number of deaths from cervical cancer in the United States has decreased substantially from 2.8 to 2.3 deaths per 100000 women from 2000 to 2015. In certain populations and geographic areas of the United States, cervical cancer incidence and death rates are still high. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomics play a central role in the epidemiology of cervical cancer rate. Higher incidence rates occur in Hispanic females at 9.4% compared to non-Hispanic white females at 7.5% and black females at 8.6%. The Lowest rates are with American/Indian Alaska natives and Asian Pacific Islanders at 6.0% respectively. Worldwide however, cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women with approximately 500,000 new cases and 250,000 deaths. In the US-Mexico border region, 1,023 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2004 (US Mexico border health commission, 2010) [1].

Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by specific types of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV). There are more than 100 types of HPV, of which more than 40 can be sexually transmitted. Among these, about 15 are cancer-causing, or high-risk, types. Two of these high-risk types, HPV-16 and HPV-18, cause about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide. HPV infection is very common, but it usually goes away on its own. Persistent HPV infections, however, can cause cellular abnormalities that sometimes develop into cervical cancer if not treated (NIH) (Figure 1) [2-4].

In 2012, The USPSTF (United States Preventive Services Task Force) made the following recommendations for cervical cancer screening: It recommended screening for cervical cancer every 3 years with cervical cytology alone in women aged 21 years to 29 years; for women 30 years to 65 years, it recommended screening every 3 years with cervical cytology alone, or every 5 years with hrHPV testing in combination with cytology (co-testing). In August of 2018, THE USPSTF updated their recommendations on cervical cancer screening. The major change in the current recommendation is that the USPSTF now recommends screening every 5 years with hrHPV testing alone as an alternative to screening every 3 years with cytology alone among women aged 30 years to 65 years. The USPSTF recommends against screening for cervical cancer in women younger than 21 years. The USPSTF recommends against screening for cervical cancer in women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and do not have a history of a high-grade precancerous lesion (i.e., Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia [CIN] grade 2 or 3) or cervical cancer [5].

Over the past decades recommendations have shifted away from screening too early (before age 21) and too often (every year) due to concerns that screening more frequently or earlier confers little additional benefit, with a large increase in harms, including additional procedures and assessment and treatment of transient lesions. Treatment of lesions that would otherwise resolve on their own is harmful because it can lead to procedures with unwanted adverse effects, including the potential for cervical incompetence and preterm labor during pregnancy (JAMA).

Research has shown that women are hesitant to embrace less frequent screening. This study assessed understanding of the pap smears/cervical cancer screening and recommended guidelines among women in El Paso (US-Mexico Border), the frequency of which they get pap smears and the reason, their understanding of HPV, and how best they would like to receive education on cervical cancer screening [6,7].

Methods

Participants

Participants of the study were all female patients who come in to be seen routinely at the TTUHSC El Paso family medicine clinic at Hague. Female patients between the ages of 21-65 were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 20 questions. The surveys were anonymous without any identifiable markers. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at TTUHSC El Paso. The surveys were conducted in a 2-month period from September to November of 2018. The total number of surveys completed during that time frame were 80. Demographically, the survey assessed for age, occupation, education, and ethnicity.

Protocol

The study aimed to gain an understanding of women’s knowledge of what the pap smear screens for who live in a US-Mexico borderland and insured. It also aimed to assess women’s understanding of the link between HPV and cervical cancer and the knowledge of their own HPV status. It assessed the frequency at which these women get their pap smears and why versus recommended guidelines and evaluated the women’s preferences of format for cervical cancer screening/pap smear education (Table 1). The participants all spoke and understood English, and the questionnaires were in English only.

| Variable | Sample population (N)(%) |

|---|---|

| (#n/N, *weighted) | |

| Age (years) | |

| 21-29 | 29/80 (36) |

| 30-65 | 51/80 (64) |

| Race | |

| Hispanic | 38/80 (48) |

| Black | 1/80 (1) |

| Caucasian | 29/80 (36) |

| Asian | 12/80 (15) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 5/80 (6) |

| Associate or some college | 4/80 (5) |

| College degree | 33/80 (41) |

| Graduate degree | 38/80 (48) |

| Knowledge of what pap smear screens for | 68/80 (85) |

| Number of participants who have had a pap | 75/80 (94) |

| Age pap should start? Answered correctly | 24/80 (30) |

| Age pap should stop? Answered correctly | 28/65 (35) |

| How often participants got a pap | |

| Yearly | 36/75 (48) |

| Every 2 years | 15/75 (20) |

| Every 3 years | 19/75 (25) |

| Why participants got pap every 1 or 2 years | |

| My doctor tells me to | 22/51 (43) |

| Peace of mind | 14/51 (27) |

| No such thing as checking too often | 4/51 (8) |

| Other (ex: h/o cysts, abnormal paps) | 13/51 (25) |

| What is HPV? Answered correctly | 66/80 (83) |

| What age should HPV co-testing start? Answered correctly | 6/80 (8) |

| Participants knew their HPV status | 55/75 (73) |

| Years for follow up pap if HPV negative? Answered correctly | 8/72 (11) |

| Pap smears on all women with hysterectomy? | |

| Yes | 46/73 (63) |

| No | 24/73 (33) |

| Don’t know | 3/73 (4) |

| Format participants want info on cervical cancer screen/pap? (>1 option) | |

| Discussions with provider the same day | 38/60 (63) |

| Printed materials/brochures | 30/60 (50) |

| Short video the day of pap smear | 11/60 (18) |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics, understanding of pap smear screening including HPV, preferred educational format. #: Number of respondents for each variable over the number who answered the question. *: Percentages for a variable may not equal 100% due to errors in rounding.

Results

Knowledge of cervical cancer screening, HPV

Most of the participants who completed the questionnaire were aware of what the pap smear test screens for and its intended purpose with 85% of the participants correctly providing the answer to: What is a pap smear? A large percentage of the participants had higher level education with 89% having a college or graduate degree and only 11% with a high school education or lower. The age range of the participants were 22 to 65 and only 5 out of the 80 participants (6%) never had a pap smear. Respondents were also knowledgeable about HPV and its relation to cervical cancer, with 83% answering the question correctly. Only 8% knew the recommended age at which HPV co-testing is recommended to begin.

Frequency of cervical cancer screen and participant’s perspective

When speaking with the participants of the survey, only 10% were aware that they had been some changes recommended with frequency of screening. However, even for those who were aware of guideline changes, they did not know what those specific changes were as it relates to the frequency of pap smear test and HPV testing. Only 30% knew at what age pap smear is recommended to start and 35% knew at what age routine pap smear should stop. The respondents were not very well-aware of the recommended follow up pap smear if HPV is negative with only 11% correctly answering a 5 year follow up for repeat pap if the HPV contesting is negative.

Out of the 80 participants only 75 had pap smears with 48% of them reporting getting a pap smear every year and 20% every 2 years and 25% every 3 years. The most common reason cited for pap smears every 1 or 2 years was: “my doctor tells me to,” at 43%. The next common reason was “peace of mind” at 27%. No such thing as checking too often was another reason at 8%. At 25% were other reasons such as history of cysts, abnormal paps in the past. Most participants felt that women should continue to get pap smears after hysterectomy regardless of the cause, with 63% of the respondents stating yes to pap smears in all women after hysterectomy. Interestingly, 21% of the participants felt that pap smear screenings should never stop until a person dies; 24% felt it should go beyond age 65 and 9% were unsure when it should stop; 35% agreed that it should end at age 65 [8,9].

Educational preferences of participants

Participants were asked if they would like to receive information about pap smear and cervical screening, and if so in what format? Most of the respondents desired to have same day discussions with the provider before the procedure (63%) and the remainder desires printed materials/brochures or short video.

Discussion

Though not part of the questionnaire, and therefore percentage cannot be provided, it is known that most participants obtain their routine pap smear at their GYN office and not at a family medicine clinic or internist.

Though participants in this population are knowledgeable about what the pap smear screens for and that HPV is linked to cervical cancer, they were not aware of the specific guidelines and recommendations for pap smear screening and HPV co-testing with the recommended frequency. Most of the participants continue to get pap smear every year with the most common reason reported that their healthcare providers are advising them as such. The question at hand with this patient population is if more women would be accepting of the 3-to-5-year interval for pap smear screening were practitioners/providers encouraging patients along those lines. It appears that provider’s themselves are serving as a hindrance to patient undergoing less frequent screening and education should be directed at both the providers and the patients.

Lastly, the participants do desire more appropriate education on pap smears and prefer to get that education on the same day that the pap smear is scheduled. Providers should consider setting aside dedicated time during the patient visit on the day of the scheduled pap smear to educate the patient on the recommended guidelines for pap smear screening and HPV testing. If after those discussions, the patient desires to proceed with more frequent screening than a reason should be sought and then patient and provider should attempt to collaborate to provide the patient with the most beneficial, cost effective, evidence-based care/screening possible.

References

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Qwens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB (2018) Screening for cervical cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 320: 674-686.

[Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed] - National Institutes of Health (1996) Cervical Cancer. NIH Consens Statement 14:1-38. [Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Screening for cervical cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement

- Schmotzer GL, Reding KW (2013) Knowledge and beliefs regarding human papillomavirus among college students at a minority-serving institution. [Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM (2005) Screening for cervical cancer: Will women accept less? The Am J Med 118: 151-158.[Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Szalacha LA, Jennifer K, Usha M, Faan R (2017) Knowledge and beliefs regarding breast and cervical cancer screening among mexican-heritage latinas.[Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed].

- Gerend MA, Shepherd MA, Kaltz EA, Davis WJ, Shepherd JE (2017) Understanding women's hesitancy to undergo less frequent cervical cancer screening.

[Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed] - Meissner HJ, Tiro JA, Yabroff KR, Haggstrom DA, Coughlin SS (2010) Too much of a good thing? Physician practieces and patient willingness for less frequent pap test screening intervals. Med Care 48: 249-259. [Cross Ref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Cervical Cancer.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences